.jpg)

As a mediation platform, DT FairBid sits at the heart of the mobile advertising value chain. In this blog post, we’ll walk you through the technical design implementation decision of how we wanted to integrate Privacy Sandbox with our mediation and the technical decisions we made along the way.

Understanding the Privacy Sandbox

Launched by Google in 2019, the Privacy Sandbox initiative aimed to introduce privacy-preserving features that protect user data while still supporting key advertising use cases. It was developed across two major environments: the web and mobile. The overarching goal was to reduce reliance on individual user data for advertising and to prevent sensitive information from being used for targeting or ad delivery.

Although the Privacy Sandbox initiative was shut down in October 2025, its API, which was published in the Android operating system in past releases (14 and 15), should remain available. Even if the work to integrate the Privacy Sandbox into DT FairBid is not relevant, discussing the implementation helps us to understand the challenges mediation platforms face. Therefore, we would like to share the experience we gained in this area.

The Privacy Sandbox for Android consisted of two main building blocks: the SDK Runtime and the Privacy Preserving APIs. Let’s explore each of these in more detail.

What Is SDK Runtime?

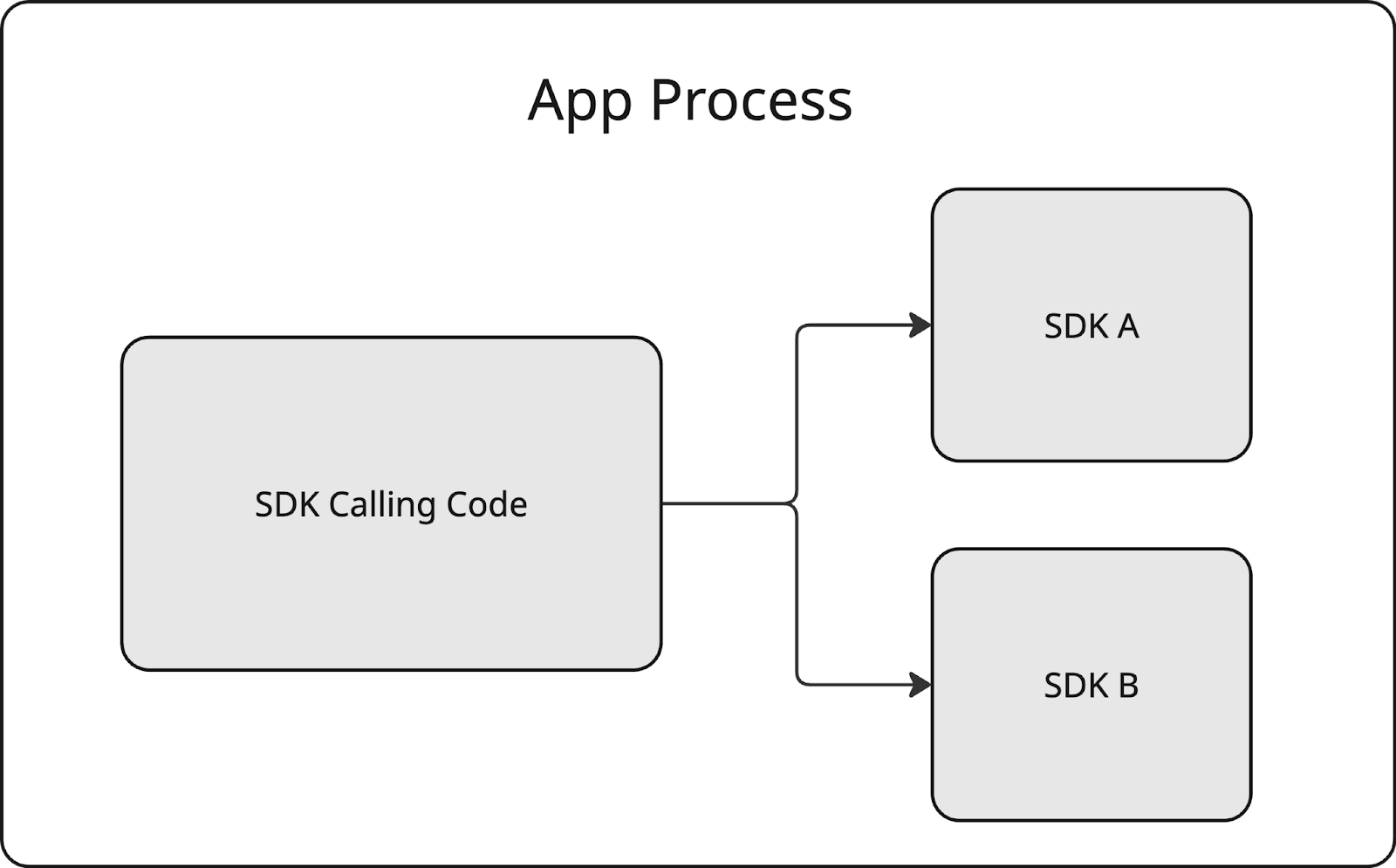

Typically, all the code for an Android application runs within a single process. This process has its own predefined set of threads, memory, and storage that can be either private or exclusive to the app’s needs. Usually, all libraries are compiled into JAR or AAR artifacts, that are embedded within the application’s binary APK file.

The SDK Runtime aimed to bring a completely different paradigm for building libraries. From then on, privacy-focused SDKs would have to run in a separate execution environment, called SDK Runtime. Shifting to this approach brought a number of new rules to adhere to:

- The SDK could have been considered another application artifact that runs in a separate process.

- The communication between the application and the SDK followed IPC rules.

- The SDKs could have operated under a set of specific permissions only.

- The SDKs had their own storage that was inaccessible to the application (and vice versa).

- The SDK running in the Sandbox could not start new activities.

- The SDK was allowed to communicate with a limited set of services.

- There was no way to define the network security configuration for libraries running within the SDK Runtime.

- There were also other runtime constraints, such as limitations on using reflection.

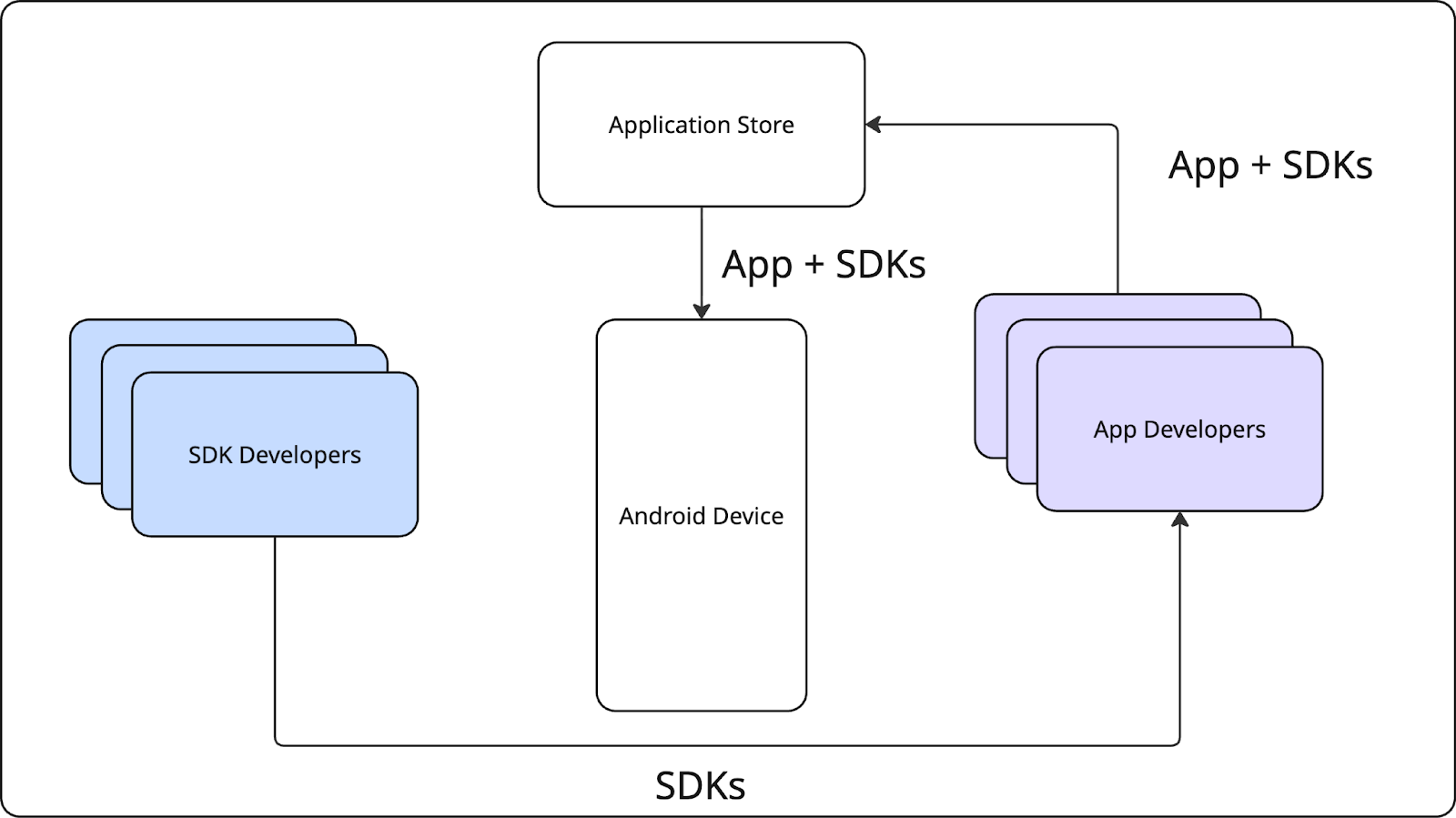

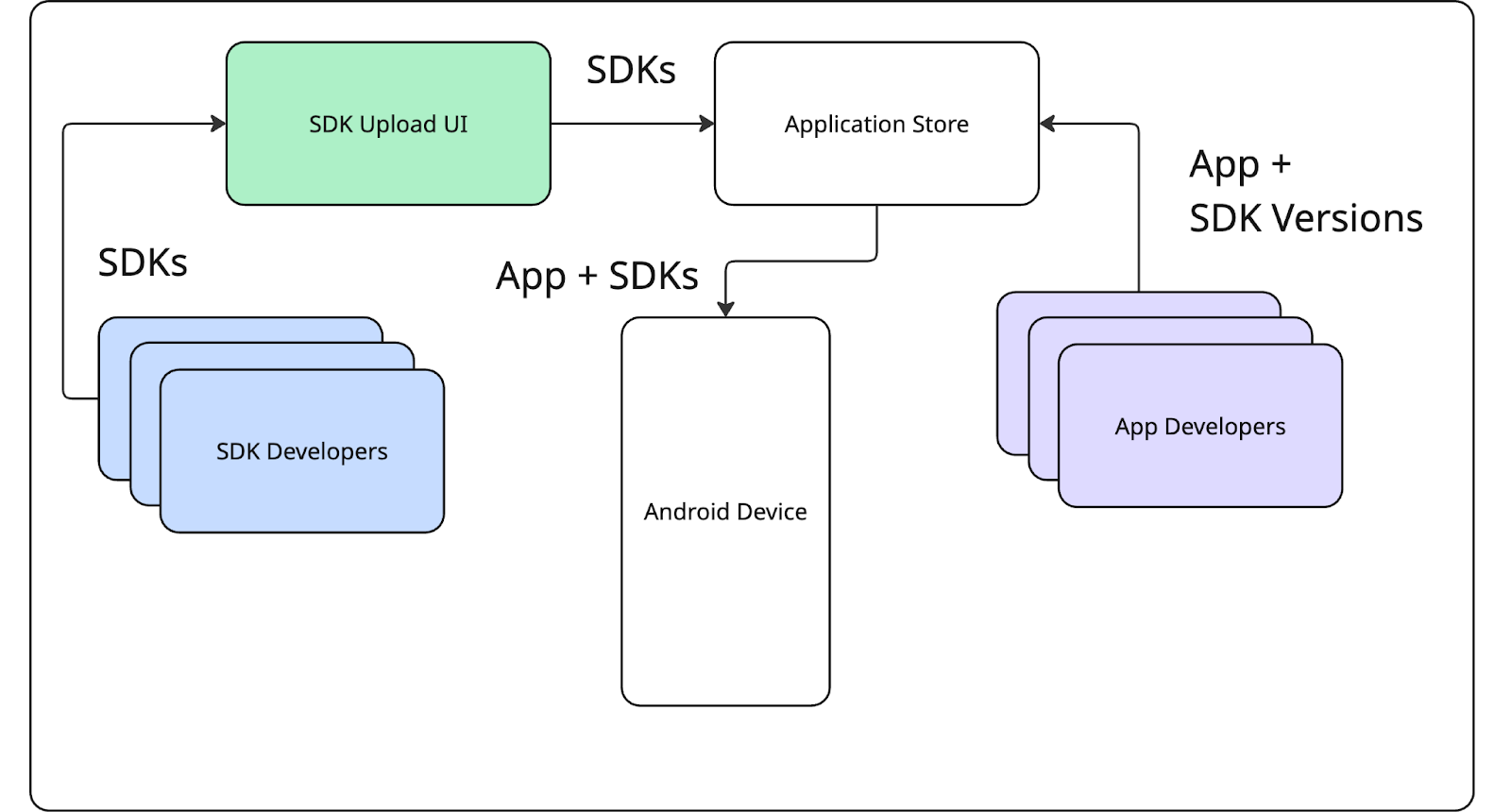

SDK Distribution

The new architecture that SDK Runtime brought was supposed to change how SDKs are distributed fundamentally. Previously, SDK developers have relied on package managers such as Maven to distribute their libraries.

With SDK Runtime, this was supposed to change significantly, as distribution was tied to the application store.

This shift introduced new opportunities and constraints. For one, SDKs were no longer bundled directly with every app. Instead, they were supposed to be managed and served as standalone modules via the app store, resolved at install time. This means that if multiple apps on a device use the same SDK, the system could share a single instance of that SDK across those apps. This has potential benefits for performance and storage efficiency. It was also supposed to allow critical SDK bug fixes to be delivered to end users without requiring app developers to update their apps. Additionally, Apps and SDKs could have been protected against fraudulent SDKs. However, this approach came with trade-offs in terms of distribution flexibility and ease of testing, especially concerning compatibility between various third-party SDKs.

Privacy-Preserving APIs

The Privacy-Preserving APIs introduced in the Privacy Sandbox were designed to support key advertising features—such as attribution, audience building, and contextual targeting—that were limited by the new SDK Runtime restrictions.

For a deeper dive into this family of APIs—Topics, Attribution, Protected App Signals, and Protected Audience APIs—and their implications for both Digital Turbine and the broader industry, we recommend reviewing the notes from our panel discussion with Google, Dataseat, and AppsFlyer.

DT FairBid and the Android Privacy Sandbox

As a mediation platform, DT FairBid doesn’t handle targeting-related features directly. Therefore, our adoption of the Privacy Sandbox centered on the correct implementation of the SDK Runtime.

Architecture and Deployment Constraints

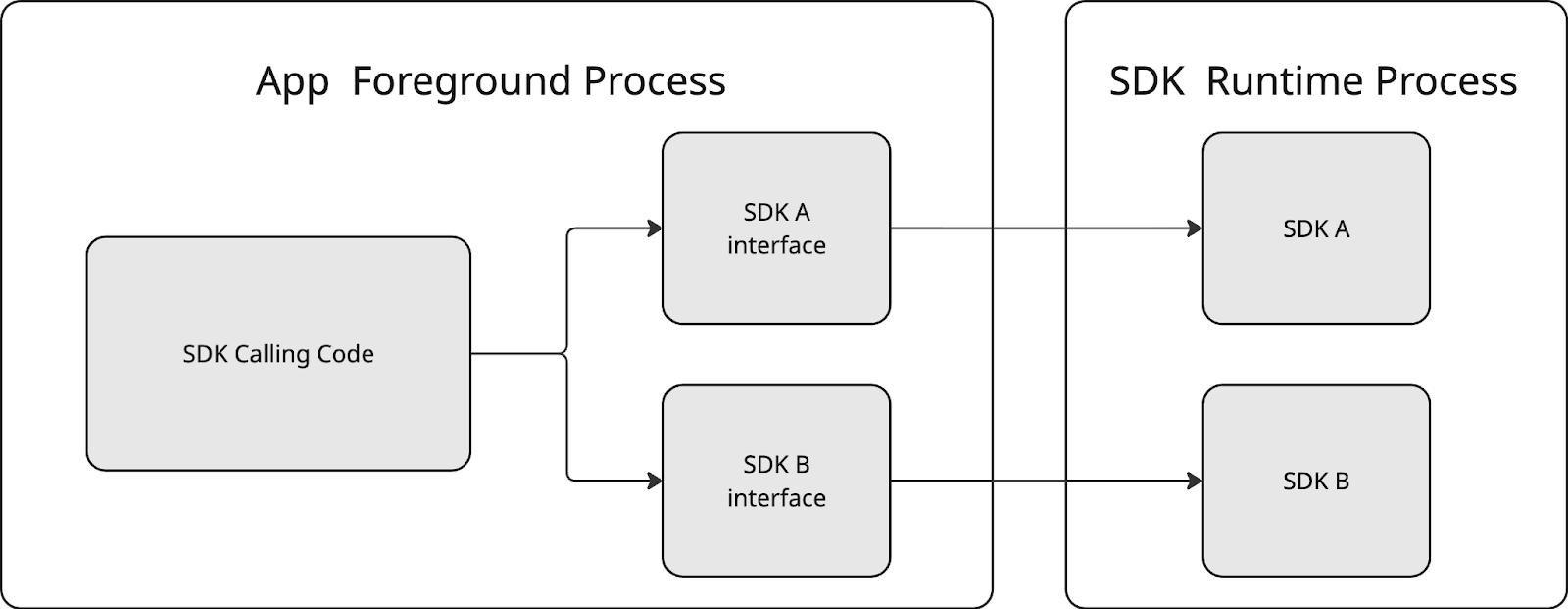

Typically, a standard SDK is structured as a single Gradle library module within the codebase, which then gets compiled and packaged into a distributable AAR or JAR file. However, building a Runtime-Compatible SDK made the development process a bit more intricate, involving three key components:

- The Runtime-Aware (RA) Module. This was supposed to be a standard Android library module. It was to serve as the primary entry point for communicating with the Runtime-Enabled (RE) Module through Sandbox APIs. Depending on specific integration requirements, this module could have functioned as a simple proxy or incorporated more complex logic, particularly when offloading unsupported operations or bridging to older SDKs still operating within the app’s process.

- Runtime-Enabled (RE) Module. It was supposed to contain the code designed to run within the SDK Runtime Environment. While technically an

androidx.privacysandbox.librarymodule type, we’ll refer to it as the Runtime-Enabled (RE) SDK going forward. - ‘‘Bundle’’ Module. Its purpose was to serve as a packaging wrapper f≠≠or the Runtime-Enabled SDK. It contained no actual code; only a single Gradle file defined its module type as

com.android.privacy-sandbox-sdkand referenced the RE SDK. This configuration was essential for generating the Android SDK Bundle (ASB) output, which was used for distribution.

The diagrams below outline the interactions between the key components that make a Runtime-Compatible SDK possible (at both development and install runtime respectively):

Let’s examine DT FairBid’s entry point in every integration and compare it with a possible runtime-enabled version to weigh some decisions down the line.

Current integration:

import com.fyber.FairBid

// Start FairBid

FairBid.start("APP_ID", context)Let’s now assume the following method is defined in the DT FairBid runtime-enabled service:

package com.digitalturbine.fairbid.re

import androidx.privacysandbox.tools.PrivacySandboxService

@PrivacySandboxService

interface FairBidSdkService {

// FairBid

fun start(

appId: String

)

}In this situation, starting DT FairBid is as follows:

import com.digitalturbine.fairbid.re.FairBidSdkService

import com.digitalturbine.fairbid.re.FairBidSdkServiceFactory

// this is generated by the shim tooling

import androidx.privacysandbox.sdkruntime.client.SdkSandboxManagerCompat

private const val FAIRBID_RE_SDK_NAME = "com.digitalturbine.fairbid.bundle"

fun startFairBid(

appId: String,

context: Context

) {

val sandboxManagerCompat = SdkSandboxManagerCompat.from(context)

val sandboxedSdk = sandboxManagerCompat.loadSdk(FAIRBID_RE_SDK_NAME, Bundle.EMPTY)

val fairbidSdkService = FairBidSdkServiceFactory.wrapToFairBidSdkService(sandboxedSdk.getInterface()!!)

fairBidSdkService.start(appId)

}Notably, the code above only starts DT FairBid; it does not account for the necessary safety mechanisms should the sandbox process terminate unexpectedly during use. These mechanisms must be handled to minimize disruption to the application’s flow.

With this in mind, we can implement all of the above within what we call the runtime-aware layer. This approach allows us to manage the complexities of code integration while still delivering a privacy-friendly SDK to our publishers. We could easily provide this:

package com.digitalturbine.fairbid.ra

object FairBid {

fun start(

appId: String,

context: Context

)

}Publishers would then integrate with us in much the same way they do with our current version:

import com.digitalturbine.fairbid.ra.FairBid

// Start FairBid

FairBid.start("APP_ID", context)Considerations for Mediation

In addition to the platform-level constraints imposed by the Privacy Sandbox, we had to consider the unique requirements and limitations of mediation. The Third-Party Network (TPN) SDKs we mediate may operate either in the Runtime Environment or within the application’s process. It’s highly probable that a substantial transition period will occur where both types coexist, necessitating careful coordination of interoperability and integration across these distinct boundaries.

Given these considerations, the primary challenge revolves around two key questions:

- Could the entire SDK project be migrated to the Runtime Environment?

- If not, which components should remain in the Runtime‐Aware layer?

We identified four primary design paths worth exploring further:

- Option 1. Building ‘‘RA TPN SDK adapters’’ on a per-need basis. This was a solution in which the DT Fairbid SDK supports RE to the extent that it can mediate RE SDKs. It’s a practical way to enable mediation in the Sandbox, but it doesn’t align with the ecosystem’s long-term vision. This is because all code would still execute within the application’s process, thus not be considered ‘‘privacy-friendly’’.

- Option 2. Moving the entire DT FairBid SDK to the Runtime Environment. This approach demanded substantial effort and carries inherent risks. However, it would ultimately lead to full compliance with the Privacy Sandbox.

- Option 3. Breaking the SDK into modules and migrating incrementally. This would reduce risk by allowing incremental design validation. Yet, the level of modularization required for the SDK Runtime clashed with our existing legacy structures. This necessitated significant refactoring before migration could even begin, adding both scope and risk to the overall undertaking.

- Option 4. Creating a second, runtime-enabled SDK. The final approach involved maintaining two separate SDK variants—a classic version and a Runtime-enabled version. This would increase development overhead, likely making the cost prohibitive.

After weighing the trade-offs of each option, our primary choice was Option 2 as it offered the most reasonable return on investment.

Below is a diagram depicting the high-level design:

Let’s take a closer look at the implications of this decision.

Inter-Process Communication

Because the SDK Runtime was supposed to run in a separate process, communication between the SDK and the app had to use inter-process communication (IPC).

On Android, IPC typically uses the Binder class or AIDL. In the early stages of the SDK Runtime project, AIDL was the default method for app-to-SDK communication. You can refer to our earlier blog post for insights into how the key SDK flows must be adapted when using AIDL directly.

To simplify the manual implementation of IPC, Google has introduced an automatically generated ‘‘shim layer’’. This layer is constructed using the SDK’s public interfaces and data classes.

You could enable this functionality by applying specific annotations to your SDK classes:

@PrivacySandboxService@PrivacySandboxInterface@PrivacySandboxCallback@PrivacySandboxValue

Each of these annotations triggers code generation via the Privacy Sandbox compiler tools, which then creates proxy classes to automatically handle IPC. These IPC calls are dispatched using Kotlin coroutines and the Main dispatcher, a setting that cannot be altered. This could potentially cause issues if your original (non-runtime) SDK depended on different threading models.

Preserving the Public APIs

To make adoption easier for publishers already using the SDK, it’s ideal for the public API to remain unchanged when migrating to the Runtime Environment. This allows for a true drop-in replacement of the privacy-friendly version.

While the RA layer makes it possible, there are subtle but important constraints—particularly around threading—that can get in the way. As a simple example, let’s look at Interstitial.isAvailable().

This method is expected to run on the main thread, return a boolean, and complete quickly.

In the Runtime Environment (RE), however, all communication happens across process boundaries, which introduces new threading constraints. To simplify this cross-process communication, Google provided a code-generation layer that uses Kotlin coroutines. As a result, any method in a @PrivacySandboxService interface that returns a value must be marked as suspend. This addition, however, breaks backward compatibility.

One workaround is to wrap the internal call using runBlocking, allowing us to call the coroutine from a non-suspending method. Blocking a method like isAvailable() is acceptable here, as it performs minimal work and is expected to return quickly. If all logic remains within the Runtime Environment, this approach is safe. Problems arise when the result depends on components in the app process, such as third-party SDKs, requiring another cross-process call. Since IPC calls from RE to RA require the UI thread, and the UI thread is still blocked waiting on the return value from isAvailable(), this results in a deadlock.

This highlights how a seemingly simple and synchronous API becomes problematic in a multi-process environment with multiple SDKs, where blocking the main thread is no longer safe or viable.

.png)

The only viable option was to make the public API call suspending, which means the existing API cannot remain fully unchanged.

No Support for Network Security Configuration

Since SDKs running in a sandboxed process can’t define a custom network_security_config.xml file, debugging network traffic through a software proxy wasn’t possible. This was a significant limitation, as mocking responses is a common testing approach. To work around it, we built an internal tool that intercepts the SDK’s network traffic and displays it directly in the UI of our internal (and local) tools, while also making sure that they use HTTPS.

UI and Backward Compatibility

During the implementation process, our engineering team also faced several issues with building the UI in the Runtime Environment.

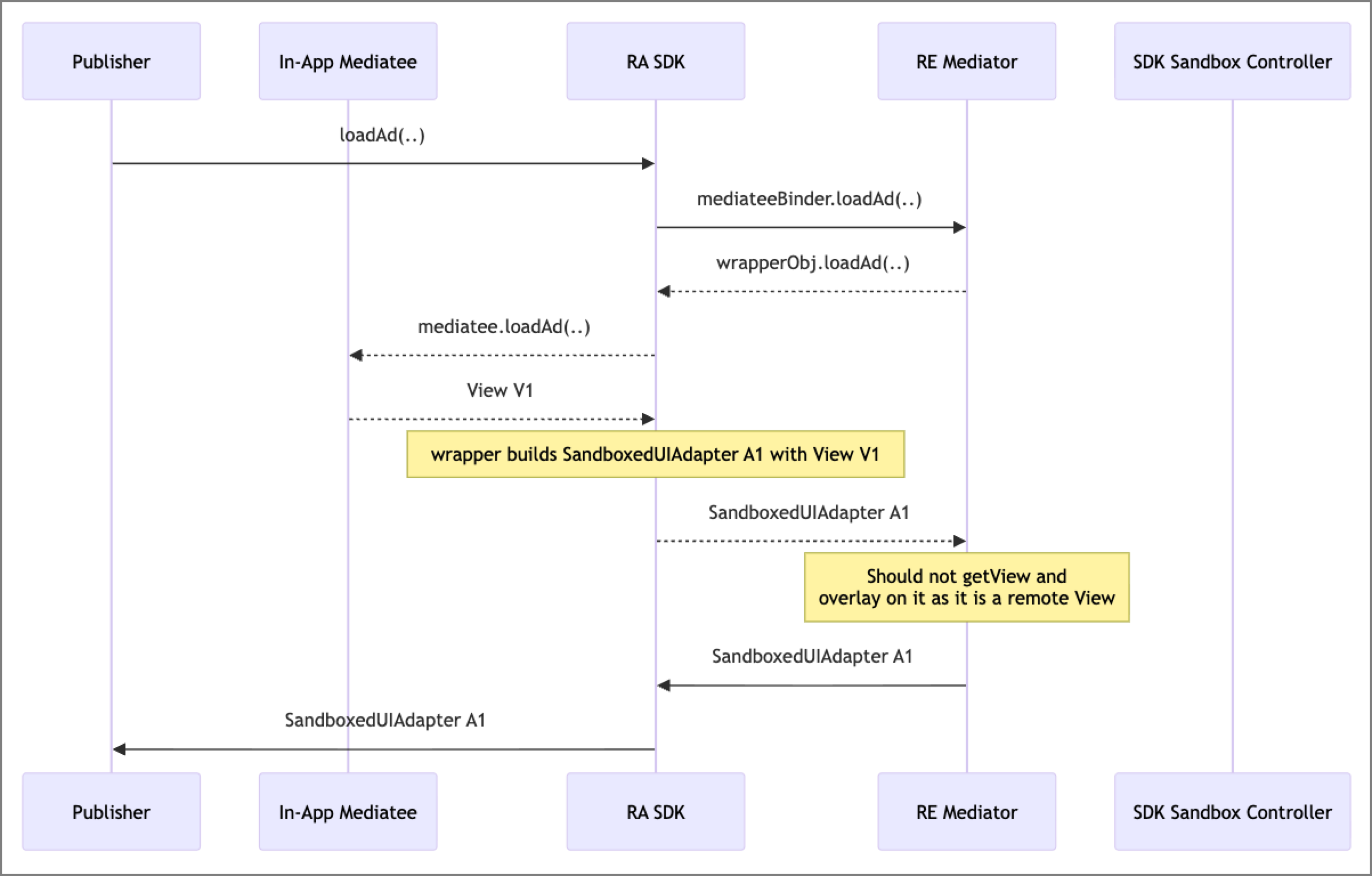

Displaying the Mediated Banner Ads in the Runtime Environment

The evolution of the SDK runtime model also led to a shift in how banners are displayed. Since the RE SDK operated in a separate process, there was a need to use a remote view rendering for the banner in order to be displayed in the app.

Fortunately, the dedicated class SandboxedSdkView supports remote banner rendering. This class, along with related components such as SandboxedUiAdapter or SessionObserver, facilitates the process to display ads directly from within the SDK Runtime.

When the client app requests a banner ad, the standard TPN mediation process begins. Once a winner is determined, its ad is then displayed.

DT FairBid has to call the third-party SDK in the standard environment to obtain the view to render (regardless of whether it is a standard or SDK Runtime environment). Once the third-party SDK provides us with a banner view, we encapsulate it within the specific implementation of the AbstractSandboxedUiAdapter class. Then this object is serialized into a Bundle, which is forwarded to the Runtime Environment, and later consumed and rendered in a SandboxSdkView. Then this view is displayed in the app.

Populating the Sandboxed Activity View

Given that the SDK running in the Runtime Environment is not able to create and start its own Activities, it is required to use the Activity provided by the ActivityLauncher. This is a pure Android OS Activity of type android.app.Activity, which means that no modern use cases (such as anything related to Jetpack or AndroidX) are allowed. There are also some other potential traps when using this approach.

Wrong Context on Android 14

During the development process, for testing purposes, we created a mock RE ad network SDK. One of its features was to display a fullscreen ad, which is based on the new Activity that has to be shown on top of the application. In order to make its view meaningful, there is a need to inflate the layout and set it as a content view—there should be no rocket science, it’s a regular flow that almost all Android applications follow. Running the same piece of code had different results on different Android versions:

- Android 15: The Activity’s view hierarchy was populated correctly, and the activity was shown.

- Android 14: The Activity’s view inflation failed except for

android.content.res.Resources$NotFoundException.

A quick investigation has revealed that in Android 14, the context used for the layout resource resolution originated from the app environment rather than the RE context, which turned out to be the reason for the crash. Android 15 has changed this behavior and streamlined the development process. However, for backward compatibility reasons, it’s important to keep in mind that the issue exists on Android 14.

Compatibility Mode: Different Classpaths, Different Classes may Appear

The same case reveals some other issues if we try to show the same ad in the Compatibility mode on Android 12. All of a sudden, the layout inflation failed once again, but with a different exception:

ClassCastException:

cannot cast androidx.constraintlayout.widget.ConstraintLayout

to androidx.constraintlayout.widget.ConstraintLayout.The reason turned out to be that there were two different dependencies containing ConstraintLayout, and different versions were used between the RE<>App environment, which were binary-incompatible. This brings another important takeaway: one should consider aligning the dependencies’ versions, even when the runtime environments seem to be different. When they are combined in a single process, it might be a reason for issues.

Working with AndroidX

If the SDK includes any UI, and if it is backed by Fragments, it might not be possible to move it to the Runtime Environment. As mentioned earlier, the Activity provided by the ActivityLauncher is very basic; it can host standard platform Fragments, but cannot be used with any AndroidX components.

If you’re fine with moving back to the plain old Fragments, you can consider backporting. However, if you stick tightly to the newer components from AndroidX libraries, which require you to also use the Activity from this set, it might be easier for you to stick with your UI in the Runtime Aware environment.

Summary

DT FairBid’s integration with the Android Privacy Sandbox, particularly the SDK Runtime, was a great technical challenge for fitting the already existing SDK code into the new requirements and limitations imposed by the target framework. Despite the subsequent retirement of the initiative by Google in response to ecosystem feedback, the architectural optimizations and cross-process communication strategies we developed remain invaluable for future-proofing our SDK against evolving privacy standards.

.jpg)

.png)

.webp)

.webp)